[We're All Keynesians Now]

Part 4 [previous]

Monetary Policy

Let us turn next to monetary policy. The ideal monetary policy prescription, which I discuss at length in my May 2007 paper ’ÄúMoney Matters," is to have stable prices over time.11 For now I will turn to an October 2008 article by Bob McTeer.12 In reference to the Fed he writes,

The Federal Reserve, as a central bank holding the reserve deposits of commercial banks (hence its name), creates bank reserves and money when it adds to its loans or any other asset. More loans on the asset side of its balance sheet are usually matched by more bank reserve deposits on the liabilities side. There is no balance-sheet constraint on that process. The Fed doesn't have to have assets to make loans.

In practice, however, the Federal Reserve over the past year has offset most of the increase in loans among its assets with decreases in its holdings of government securities. In other words, it has neutralized or sterilized the monetary impact of its lending—meaning the impact on bank reserves—with open market sales of government securities.

What he is saying is that while the bank's balance sheets have grown very rapidly, bank reserves have not grown because they have been offset by neutralization or by selling off of treasury securities. He continues,

If the purpose of monitoring the Fed's balance sheet is to gauge the expansionary or inflationary implications of its lending, or other actions, a more appropriate way to do it is not to focus on growth of total assets and liabilities, but to focus directly on bank reserves. Bank reserve deposits at the Fed together with currency outside the banking system make up what economists call the monetary base, or high-powered money.

Rapid growth in the base, primarily bank reserves in practice, gives the banking system the ability to make more loans and investments, and hence create more deposit money. The effective marginal reserve requirement is about 10%. So each dollar of new reserves will eventually add about 10 dollars of money. Think of bank reserves as wholesale money and bank deposits as retail money. Exactly which bank deposits you include give different definitions of money, M1, M2, MZM, and so forth.

What he is talking about here is bank reserves being the sort of base money that allows for expansion. I've been focusing on the monetary base from time immemorial. He goes on to say, "Yet most believe that over the long run, inflation, to quote Milton Friedman, 'is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.' But, I digress"

That relationship means that other things being equal, increases in Fed assets tend to increase bank reserves, while increases in other Fed liabilities tend to reduce bank reserves. Therefore, when the Fed offsets an increase in one of its assets (loans) with a decrease in another of its assets (treasury securities), there is no net effect on bank reserves. The importance of his comment is that with all these TAFs, TALFs, TSLFs, PDCFs, and MMFs, there exists no linear relationship between any of these programs and bank reserves. Bank reserves are what they are because the Fed wants them to be there. Continuing with Bob's article,

That was the case over most of the past year. Fed lending had virtually no impact on bank reserves. However, beginning in September 2008, that changed dramatically. In recent weeks bank reserves, the monetary base, and other monetary assets have grown rapidly’Ķ One could easily argue that the Fed overdid its sterilization for most of the period, which made monetary policy too tight. As for the recent period, the extremely high growth is probably appropriate, and not inflationary, while credit markets remain frozen and velocity continues to fall. It is something that will have to be corrected as we return to normal in credit markets, or accelerating inflation will become a serious concern.

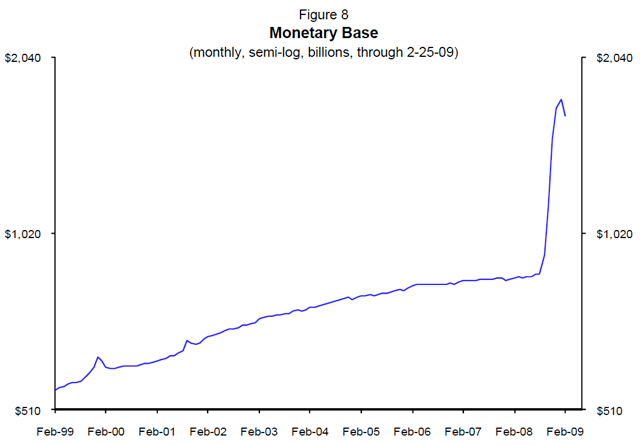

Over the past year the Fed’Äôs balance sheet has grown from about $904 billion to just over $1.9 trillion, having reached a high of about $2.3 trillion in December 2008, a more than doubling of the Fed's assets. Total reserves, which are liabilities to member banks, stood at $97.8 billion a year ago, while as of January 28, 2009, total reserves stood at $916.3 billion.13 That is almost a 10-fold increase in liabilities to member banks. The monetary base has grown from about $860 billion in January 2008 to about $1.75 trillion today (Figure 8), a more than doubling of the monetary base.14 There has been no thought given to taking these reserves out, even though, repeating Milton Friedman, "Inflation is everywhere and at all times a monetary phenomenon."

I think the Fed does not have a clue what it is doing. This is the largest increase in the monetary base in U.S. history. It is incredible. There is no sign that they understand how to control this amount of money, and as a result, I would expect a lot of inflation in the U.S. economy in the next 18 to 24 months.

When the inflation comes, interest rates will rise very sharply, especially in the long bond area, as there will be a huge inflation premium on interest rates. The government will have more and more difficulty financing its deficits. I have never seen a monetary policy deviate more from the ideal monetary policy; this is much worse than in the 1970s. Higher interest rates will result in capitalized economic profits falling relative to stock prices, rather than stock prices rising relative to capitalized economic profits.

8. Robert Barro, "Government Spending Is No Free Lunch," Wall Street Journal, January 22, 2009; John Taylor, "How Government Created the

Financial Crisis," Wall Street Journal, February 9, 2009; Arthur B. Laffer, "The Age of Prosperity is Over," Wall Street Journal, October 27, 2008.

9. James Gwartney and Richard Stroup, "Labor Supply and Tax Rates: A Correction of the Record," American Economic Review, 1983.

10. "Barack Obama-san," Wall Street Journal, December 16, 2008.

11. Arthur B. Laffer and Kenneth B. Petersen, "The Federal Reserve and the Economy," Laffer Associates, March 5, 2008.

12. Bob McTeer, "The Fed's Balance Sheet," Forbes, October 29, 2008.

13. Numbers are for St. Louis Adjusted Reserves: series reached a high of $941.16 billion on January 14, 2009, and currently stands at $762.19 billion.

14. As of February 25, 2009, the monetary base was about $1.621 trillion, down from a high of $1.75 trillion recorded two weeks earlier.

[next]