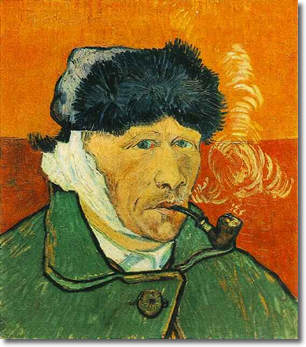

Self-Portrait with Bandaged

Ear and Pipe

Arles: January, 1889 (Chicago, Collection Leigh B. Block) F 529, JH 1658

|

“La mutilation sacrificielle et l’oreille coupée de Vincent Van Gogh,” Documents, second year, 8 (1930), 10-20; rpt. Œuvres complètes, vol. I, ed. Denis Hollier (Paris: Gallimard, 1970), 258-70. English translation: Georges Bataille, “Sacrificial Mutilation and the Severed Ear of Vincent Van Gogh,” trans. Allan Stoekl, Visions of Excess, ed. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 61-72. |

| . . . Vincent Van Gogh, who carried his severed ear to the place that most offends polite society. It is admirable that in this way he both manifested a love that refused to take anything into account and in a way spat in the faces of all those who have accepted the elevated and official idea of life that is so well known. Perhaps the practice of sacrifice has disappeared from the earth because it was not able to be sufficiently charged with this element of hate and disgust, without which it appears in our eyes as servitude. The monstrous ear sent in its envelope, however, abruptly leaves the magic circle where the rites of liberation stupidly aborted. It leaves along with the tongue of Anaxarchus of Abdera, bit off and spat bloody in the face of the tyrant Nicocreon, and with the tongue of [Z]eno of Elea spat in the face of Demylos . . . both of these philosophers having been subjected to atrocious tortures, the first crushed while still alive in a mortar. (70-71) |

Self-Portrait with Bandaged

Ear and Pipe |

| the sun in its glory is doubtless opposed to the faded sunflower, but no matter how dead it may be this sunflower is also a sun, and the sun is in some way deleterious and sick: it is sulfur colored [il a la couler du soufre], the painter himself writes twice in French. (66) |

Wheat

Field with Reaper and Sun Saint-Rémy

|

| In

the last issue [of Documents] Bataille devoted a long article to

van Gogh that established a connection between the business of the cut ear

and the theme of the sun, which is present in the painter’s work sometimes

directly and sometimes obliquely. We are aware of how heavily the theme

of blinding sun, associated with sacrifice as projection out of oneself

into ecstasy or into death, bore on the entire work of the writer who, giving

way on certain points but intractable when it came to confronting the reader

with something confusing, was the leader of the game during that strange

match of whoever-loses-wins, the Documents venture. Michel Leiris, “From the Impossible Bataille to the Impossible Documents,” Brisées, trans. Lydia Davis (San Francisco: North Point, 1989), 246.

|

Still

Life: Vase with Five Sunflowers |

|

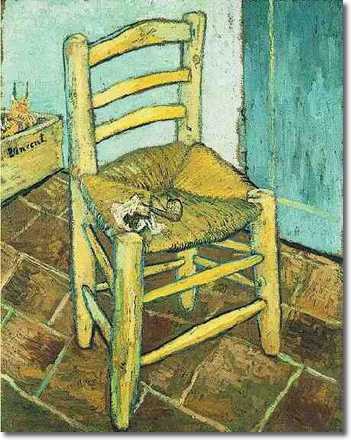

These two paintings are especially significant in that they date from the period of the mutiliation. One need only look at the reproductions of the paintings to see that they represent not just an armchair or a chair, but the virile personae of the two painters. Due to a lack of information, it is difficult to interpret these paintings with perfect certainty; one cannot, however, fail to be struck by a contrast to Gaugin’s advantage: an unlit pipe (an extinguished and suffocating hearth) is opposed to a lit candle, a tawdry pouch of tobacco (a dessicated and calcified substance) is opposed to two novels covered with brightly colored paper. The difference is all the more charged with troubling elements in that it corresponds to the period in which Van Gogh’s feelings of hatred for his friend were so extreme that they led to a definite break, but the hatred directed against Gaugin is only one of the most bitter forms of an inner rending whose theme is generally found in all of Van Gogh’s mental activity. (64-66) |

|

|

|

The relations between this painter (identifying himself successively with fragile candles and with sometimes fresh, sometimes faded sunflowers) and an ideal, of which the sun is the most dazzling form, appear to be analogous to those that men maintained at one time with their gods, at least so long as these gods stupefied them; mutilation normally intervened in these relations as sacrifice: it would represet the desire to resemble perfectly an ideal term, generally characterized in mythology as a solar god who tears and rips out his own organs. (66)