Contact: Mark Abolins, Ph.D.

Faculty webpage

What is the Nashville Rift?

The Nashville Rift formed more than 500 million years ago when the Earth stretched in what is now northwestern Alabama, central Tennessee, and south-central Kentucky. When the Earth stretched, faults formed and bodies of liquid rock rose from deep within the Earth, solidifying into the igneous rock gabbro at relatively shallow depths within the ground. Later, more than 1.4 km (0.87 miles) of sediment covered the rift.

Some scientists think the rift formed as early as 1.1 billion years ago and that the rift is shorter, terminating in central Tennessee at its northern end.

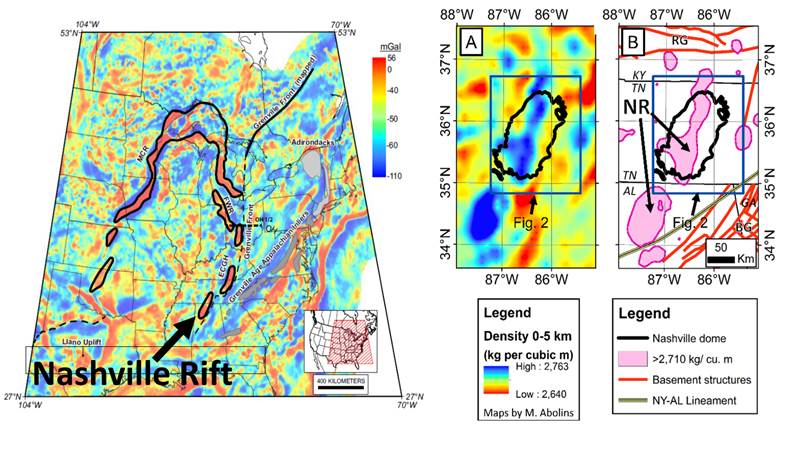

LEFT: Nashville Rift in relation to other buried rifts in the North American interior. Rifts superposed on Bouguer gravity. Figure from Stein et al. (2018). RIGHT: Nashville Rift (NR) defined by elevated upper crustal density Levandowski et al. (2016). Nashville Dome from Stearns and Reesman (1986). Basement structures from Marshak et al. (2017). NY-AL Lineament from Steltenpohl et al. (2010). KY-Kentucky, TN-Tennessee, AL-Alabama. Figure from Abolins et al. (2018).

Why do some scientists think a rift is down there?

The Earth’s gravity pulls a little more strongly above a linear belt of the Earth that runs from northwestern Alabama to south-central Kentucky. In the U.S. Midwest and many other places around the world, buried rifts coincide with gravity highs somewhat like this one.

Could dangerous earthquakes happen on rift faults?

A M2.6 earthquake happened within or immediately west of the Nashville Rift on 7 July 2001 (local date) and was felt by some residents on the east side of the central Tennessee community of Franklin. This earthquake startled some residents but no damage was reported. Given what is known and what isn’t known about the Earth, there is an extremely small but non-zero chance of dangerous shaking at many locations around the world. However, there is currently almost no earthquake activity within the Nashville Rift. This contrasts with larger amounts of earthquake activity – and more earthquake hazard – to the west in the New Madrid Seismic Zone and to the east in the Eastern Tennessee Seismic Zone.

*** Local M2.8 earthquake felt on MTSU campus on 1/15/19. USGS website. ***

*** Dr. Abolins provides context on WSMV Channel 4 (NBC). ***

Does the Nashville Rift explain anything that scientists can observe at

the surface?

Yes, the Nashville Rift likely played a major role in the geologic history of central Tennessee because rift faults reactivated (moved again) during major episodes of Appalachian uplift. These underground movements caused relatively small but geologically very significant uplift of the Earth’s surface. These underground movements also caused rocks to bend and break at the surface. In central Tennessee, the Nashville Rift coincides with the Nashville Dome. The Nashville Dome is an area in which rocks were bent long ago into an upside-down bowl. Later, the center of the dome eroded away creating the Central Basin, an area in which the land surface is lower in elevation. The rift also coincides with major changes in the thickness and composition of sedimentary rocks exposed at the surface. Geophysicist Will Levandowski and MTSU Professor Mark Abolins are preparing a manuscript describing how knowledge about the Nashville Rift adds to the understanding of younger geologic features.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this work were funded by NSF EAR1263238 to Dr. Mark

Abolins and Dr. Heather Brown and a pair of MTSU Faculty Research and Creative

Activity grants (Summer 2013 and Summer 2018) awarded to Dr. Mark Abolins. The opinions expressed in this website are

those of the author and are not those of NSF or MTSU.

A special “thank you” to all who helped in some way small or large with some facet of this work. Faculty/professionals: Dr. Will Levandowski, Dr. Albert Ogden, Dr. Clay Harris, Dr. Ron Zawislak, and Josh Upham. Undergraduate students: Shaunna Young, Joe Camacho, Amber Han, Jonathan Flores, Rachel Bush, Alex Ward, Mark Trexler, Matt Cooley, Christiana Rosenberg, Brie Paladino, Laura Hoefer, Nate Johnston, Leanna Davis, Rachel Schultz, Brandi Bomar, Indya Evans, Jason Pomeroy, Kyle Wiseman, Mark Olivera, and students enrolled in the Fall 2014 and Spring 2017 MTSU Field Methods in Geology courses.

Revised 1/27/2019