Langston,

Psychology of Language, Notes 4 -- Speech Production

I. Goals.

A. Production errors.

B. A production model.

II. Production errors. We need to rethink the way

we’re studying language. Instead of thinking about how you

understand

language, we’re going to look at how you produce language. The

main

way to tell what’s happening in production is to look at the kinds of

errors

that people make.

A. Some of the more common types of errors:

1. Shift: One speech segment moves from its appropriate

location “That’s so she’ll be ready in case she decide to hits it.”

2. Exchange: Two units change place “Fancy getting your

model renosed.”

3. Anticipation: A segment is produced too early “Go ahead,

bake my bike.”

4. Perseveration: A segment gets repeated “He pulled a

pantrum.”

5. Addition: Add a segment from somewhere “I didn’t explain

this clarefully enough.”

6. Deletion: A segment gets left out “I’ll just get up

and mutter _intelligibly.”

7. Substitution: Substitute a related segment for the

intended

segment “At low speeds it’s too light.”

8. Blends: Two possible segments become blended into one

output “That child is looking to be spaddled (spanked/paddled).”

B. Where do errors occur? All levels of production

(phonological,

syntactic, lexical insertion...). But, you don’t see mixes of

levels.

So, for example, phonological errors usually occur in syntactically

correct

sentences.

C. Common properties of errors:

1. Elements that interact come from similar environments.

Beginnings change with beginnings, ends with ends, etc.

2. Elements that interact tend to be similar. Consonants

don’t replace vowels.

3. Even when errors produce novel linguistic items (spaddled)

they’re consistent with the rules of the language (in this case

spelling

rules).

4. Errors will have the same stress pattern as the thing they’re

replacing.

D. Where do errors come from?

1. Freud: Errors are Freudian slips. It’s a way to

look at what someone is really thinking. You have a lot of stuff

going on in your unconscious, and some of it’s bad and being

repressed.

But, repressed stuff sneaks out in production errors. For

example,

there’s a cartoon with a king and a queen, and the king is saying “Good

morning beheaded... er, beloved.” The slip is that she’s about to

be beheaded...

Experimental evidence: Take male subjects and put them in a room

with a scantily clad female experimenter. Errors like saying

“fine

body” instead of “bine foddy” when reading out loud under time pressure

indicate that errors are based on impulses from the Id.

2. ReverseSpeech: To fit with the unconscious message being

uttered in reverse, the forward message will sometimes need to be off a

bit. More on this later.

3. Psycholinguistics: The errors come from the complexity

of producing language. A lot of stuff is happening, it’s

happening

fast, and it’s happening in a system with limited capacity. All

of

that makes errors likely. What is the production system?

Top

III. A production model. The basic model has four

parts:

A. Conceptualize: This buys into the language of thought

idea (that thoughts are in mentalese, not language). You have to

have a thought before you can begin to produce an utterance.

B. Form a linguistic plan:

1. Identify meaning: It’s kind of like looking in a

dictionary

backwards. You have a thought you want to express, and you look

for

definitions that match the thought.

2. Select syntactic structure. We will have a rule in our

phrase structure grammar that says S -> NP + VP (a sentence is a

noun phrase

plus a verb phrase). The real grammar has many possible sentence

types. Choose one here and build the tree (like Chomsky’s toy

grammar).

3. Generate an intonation contour. Fans of Seinfeld will

know that if Jerry’s not sure if he’s invited to a party and the host

says

to Elaine “Why would Jerry bring something?” it’s not the same

as

“Why would Jerry bring something?” In the one case,

Jerry’s

probably not invited. In the other case, he’s invited, just not

expected

to bring anything. This step is where you lay out stress

patterns.

4. Insert content words: Put in the words.

5. Form affixes and function words.

6. Specify phonetic segments: Figure out how it’s

pronounced.

7. Edit: Look at the “darn bore” task. People are

much more likely to say “barn door” after the biasing context than

“bart

doard.” That’s because “barn door” makes words (even if it’s not

the intended utterance), but “bart doard” doesn’t. So, people

probably

have an editing function at the end of the plan to check for basic

errors.

Two things to say about this model:

1. Errors support dividing the plan into these particular

steps.

For example, if you say “Stop beating your brick against a head wall”

it’s

a problem at only stage four (insertion). Everything else seems

to

have gone off OK.

2. Errors support this particular sequence. For example,

if you say “It certainly run outs fast” and pronounce the ‘s’ in “outs”

as /s/, it indicates that the sound part came after the affix part

(because

if the sound came first, the ‘s’ would sound like /z/, since that’s how

it would sound in “runs”).

C. Implement the plan: Once you make a plan, you have to

say what you came to say. What do I want to say about this?

That planning and production seem to go in cycles. If you graph

time

on the x-axis, and amount produced on the y-axis, it looks like people

plan a while, say that much, plan some more, say some more, etc.

Why? Because it’s a hard task, which probably maxes out working

memory

all the time. You have to do it in cycles.

D. Self-monitoring: Obviously, some errors get by the

editing

step. What happens when errors get out? Stop and make a

self-repair.

Three steps:

1. Self-interruption: Signal that you’ve spotted the error

and stop. A procedure to get a lot of this is to have people

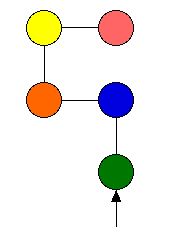

describe

colored diagrams (like the one below). They have to describe them

so someone else can draw them. People make a lot of mistakes, and

have to correct themselves a lot.

a. Some statistics about when people interrupt themselves:

Interrupt within a word: 18% of the time “We can go straight on

to

the ye-, er pink.” Interrupt after the word: 51% “Straight

on to green- to red.” Interrupt at some later point: 31%

“and

from green left to pink, er from blue left to pink.”

b. How do they interrupt themselves? Utter an editing

expression

to indicate trouble (generally “uh”).

c. Self-repair: Fix the problem.

Top

Psychology of Language Notes 4

Will Langston

Back to Langston's Psychology of Language

Page