Stagflation is an unfortunate condition in which unemployment and inflation are both too high and rising. The disease has created a dilemma for policy because attempts to slow inflation by restrictive fiscal and or monetary policy will create more unemployment. Conversely, attempts to reduce unemployment by expansionary policies comes at the risk of more inflation. What then, can be done? Perhaps a review of the history of policy in the stagflation era will provide some useful tips.

With almost daily increases in the cost of imported oil, we are once again threatened by a severe bout of stagflation. Oil price increases affect the economy on both the demand and the supply side. On the supply side, higher energy costs raise production costs. That, in turn, forces firms to raise prices. On the demand side, a rise in the cost of energy affects consumers as if they were suddenly confronted by the imposition of a heavy excise tax. Consumers must pay more for the energy they use and thus have less income remaining to purchase other things.

Try as hard as they might, President Jimmy Carter and his economic advisers were unable to devise policies to stop the inflation that had been set in motion by the quadrupling of oil prices by the OPEC cartel in 1974. All hope for an end to accelerating inflation was subsequently torpedoed by another doubling of the price of internationally traded oil in 1979.

William Miller had been appointed to be Federal Reserve Chairman. Unlike most Federal Reserve Governors, Miller was an industrialist who had met payrolls and was deeply troubled by unemployment as well as inflation. His concern for jobs caught him in a nasty dilemma. Inflation had begun accelerating after 1976. But at the same time the economy had not yet fully recovered from the recession of 1975. Controlling inflation called for restrictive monetary policy. But that would be at the cost of slowing recovery. Supporting recovery meant increasing the money supply in a way that would accommodate rising inflation. But that would permit inflation to accelerate. And that, unfortunately, is what happened.

Never happy with his Fed job, Miller left and was succeeded by Paul Volker, a Wall Street banker, who had been instructed by President Carter to slow the inflation. Volker promptly announced that henceforth the Fed would no longer target interest rates and would focus instead on growth of the money supply. From 1979 to 1981, growth of the money supply was limited to an annual rate of 6.9 percent. Over that same period of time, nominal GDP grew at a rate of 10.5 percent. With the money supply growing far more slowly than spending, it was inevitable that there would be a sharp escalation of interest rates. In response, the economy not only slumped but went into the deepest recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The unemployment rate averaged 9.7 percent in 1982 and rose to more than 10 percent at the end of that year. Very few expected such a major calamity.

The severity of the recession caught most economists by surprise. It was generally assumed that the higher interest rates would slow business investment and credit-dependent consumer spending. That would slow the economy, and that would slow inflation. The spending slowdown would also cause the economy to import less. That traditional line of thinking proved to be erroneous. It ignored the new world of flexible exchange rates and highly interest-rate responsive international short-term capital.

Short-term capital in search of the higher U.S. interest rates flowed into the economy in huge amounts. In order to purchase the higher-yielding U.S. securities, foreign investors required dollars that they obtained by flooding the foreign exchange market with their own currencies. This behavior caused the dollar to appreciate sharply. That had the effect of reducing the cost of imports to Americans while increasing the cost of our exports as seen by others. The result was a massive swing in the balance of trade as imports replaced domestic production while exports stagnated. The severe recession was the result. Inflation declined dramatically under the pressure of cheap imports and excess capacity in export industries.

As the U.S. slid into recession, most other industrial countries were suffering from accelerating inflation caused, in large part, by the opposite of what was happening in the United States. As the dollar appreciated, the value of foreign currencies fell. Foreign productive capacity was strained by increases in the American demand for foreign goods as well as from the decline in competition from expensive American exports. Thus, inflation in the United States was abated largely because it was exported to other countries. Attempting to stem the depreciation of their currencies and the inflation that went with it, foreign monetary authorities purchased their own currencies, thereby decreasing their money supplies. But all countries cannot appreciate their currencies simultaneously. Competition to do so by reducing money supplies produced a worldwide shrinkage in money supplies that spread the recession that began in the United States to much of the rest of the world.

The table was now set for Ronald Reagan and his brand of economics. The recession reached bottom in the winter of 1982. The recovery that followed was fueled by income tax reductions and doubling of defense spending. These measures converted Jimmy Carter’s modest 1979 federal deficit of $11.3 billion into a deficit of $190.8 billion in 1986. And the deficit would have been a lot higher had it not been for a doubling of Social Security payroll taxes from $148.9 billion in 1979 to $297.5 billion in 1986. While the expansionary fiscal policies were promoting rapid recovery, they were, in some respects, disappointing. Interest rates remained high, and that was interfering with business investment and economic growth. Investment rose at a nominal rate of 6.1 percent, a meager result that was contrary to the expectations created by the advocates of supply-side economics.

It was clear that interest rates had to be lowered if the growth of investment was to be raised. However, that would necessitate a sharp reduction in the federal budget deficit. But how? The income tax cuts were regarded as sacred, and there would be no backing down on defense spending. The solution was to erect a smoke screen pretending, for public consumption, that Social Security was in trouble and that payroll taxes would have to be raised. Alan Greenspan, a former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Gerald Ford, orchestrated the gigantic hoax that Social Security’s survival necessitated higher payroll tax receipts. Greenspan knew that the purpose of the tax increases was to reduce the budget deficit. The extra revenue would be used by the Treasury to pay its various bills. Social Security would get nothing, and that was the intention.

Throughout his career as chair of the Federal Reserve, Greenspan took every opportunity to raise phony alarm bells about Social Security, proposing benefit reductions, increases in retirement age, and reducing the annual cost-of-living adjustment. Partial indexing of benefits would create a steady reduction in the real value of benefits. If inflation proceeds at an annual rate of 5 percent while benefits are raised at a rate of 3 percent, one dollar of benefits today will be worth 91 cents in 5 years and 82 cents in 10 years. Partial indexing was another innocent-sounding proposal that would create progressive hardship for elderly persons.

For the most part, it was assumed by liberal economists that, as chair of the Federal Reserve, Greenspan could be counted upon to do what Wall Street wanted him to do. It therefore came as an unpleasant shock to liberals when Bill Clinton reappointed Greenspan to another term as Fed chair. Although neither seems to have been credited, it was a felicitous collaboration between the President and the chair that paved the way for the noninflationary growth of the economy during the Clinton 1990s.

Real GDP declined in 1991, but consumer prices were once again on the rise. The stagflation syndrome had returned. The policy dilemma created by stagflation had returned: boost the economy with expansionary policy and watch inflation accelerate, or attempt to slow inflation with restrictive policies and watch unemployment increase.

Motivated by rising unemployment, members of Congress pleaded with chair Greenspan to lower interest rates by easing up on the Fed’s tight reign on the money supply. Greenspan agreed that interest rates were too high but resisted the plea because increasing the money supply would re-kindle inflation. In his view, the right way to reduce interest rates was to reduce the Federal budget deficit. Greenspan let it be known that monetary conditions would remain tight as long as Congress and the President did nothing to reduce the deficit. He had no intention of giving Congress an excuse to do nothing about the deficit. Policy was at an impasse.

When Bill Clinton became President in 1993, he inherited an economy in which unemployment and inflation were both too high. Interest rates would have to be lowered if growth was to be revived. Clinton knew that Federal Reserve Chairman Greenspan would have to be either removed or accommodated. Clinton chose the latter course. To the chagrin of liberals, including the present author, he reappointed Greenspan to another term as chair of the Federal Reserve.

The President and the chair seemed to have arrived at a tacit understanding, whether spoken or unspoken. The President would have to take major steps to reduce the federal budget deficit. Income taxes were to be raised, and federal spending had to be tightly controlled. In return, Greenspan would loosen his tight reign on the money supply. Clinton asked the congress to legislate an income tax increase. This, and other fiscal measures, permitted the Fed to loosen its monetary stranglehold. In combination, the policy changes put downward pressure on interest rates that paved the way for the rapid and sustained noninflationary growth the country enjoyed during the years of the Clinton administration.

Changing the policy mix was the magic trick. Monetary policy would be eased, while fiscal policy would become more tightly restrained. Usually such a combination of policy mix changes would be seen as working at cross purposes, one canceling out the other. The spending effects canceled each other out, but both policy changes had the effect of lowering interest rates, thereby creating a favorable climate for growth of business capital spending. The odd couple of Clinton and Greenspan deserve high marks for creating an environment that made this possible.

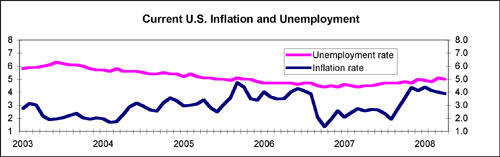

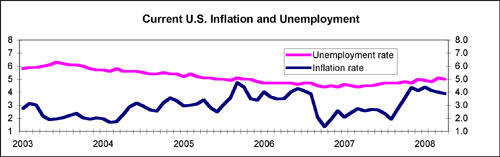

Stagflation is with us again today. Growth has virtually stopped, and inflation is again on the rise. Once again, the principal cause is the sharp and continuing increase in the cost of oil. This is hitting the economy on the demand side, as consumers buy fewer goods because they have to pay more for gasoline, and on the supply side, as rising energy prices work their way into the cost structure. Will there be another odd couple to help the future economy out of the dilemma, or will inflation and slow growth once again characterize the American economy in years to come?

Thomas Dernburg is Emeritus Professor of Economics, the American University, and a former holder of the Chair of Excellence in Free Enterprise at Austin Peay State University.

BERC Graph Data Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics