Langston,

Cognitive Psychology, Notes 12 -- Language--Meaning

I. Goals:

A. Where we are/themes.

Meaning:

B. Literal.

C. Inferences.

D. Figurative Language.

E. Pragmatics.

Understanding:

F. Readers’ knowledge.

G. Working memory revisited.

H. Outline of a basic discourse model.

I. Mental models.

J. Wrap-up.

II. Where we are/themes. I have two goals for this

lecture:

Meaning: When we talk about the “meaning” of a sentence, it can

actually be represented at multiple levels. What we'll do is look

at the kinds of information represented at each level. We'll

start

with literal. Then we'll talk about going a little beyond literal

by adding information to the representation. Then we'll go way

beyond

literal by looking at figurative language (the meaning is different

from

the words). Finally, we'll talk about pragmatics (the meaning

isn't

in the words at all).

Understanding text. When we're through with meaning, we're going

to move on to talk about extracting the meaning from texts. What

do we have to talk about? We have to extract the information, we

have to make some sort of representation, and we have to hook up the

ideas

in that representation. We need to store that away so we can

recall

it later, and we need to elaborate it with inferences.

What you're going to see will look a lot like two lectures piled

together.

That's because it is. The theme of this unit is to take all of

the

work we've done and integrate it to understand an interesting question.

Meaning: What is the meaning of a sentence? This

is a hard concept to define, and a hard concept to study. To make

it less complicated, I'm going to divide it into four parts.

Top

III. Literal meaning. This is what the sentence

is about in the strictest sense. This kind of meaning can be

broken

down as well.

A. Verbatim meaning: Basically, memorize the text.

You don't process it or try to understand it, just memorize it.

This

type of meaning representation is very poor. In some contexts

this

is all you have to rely on, so you will see people form verbatim

representations.

Usually, this is only used for rote memorization. If you think

about

the Star Spangled Banner (if you happen to know it) the meaning isn't

really

what you're reciting, it's the words, cued one from the other like a

behaviorist

sentence. The things whose meaning you understand aren't usually

remembered word-for-word.

B. Deep structure: It's a fact that people remember the

gist of what they read better than the exact words. One idea for

what the gist might be is to remember deep structures as in

transformational

grammar. So, if you hear “Alice plays the tuba” you remember

something

like “Alice play tuba”, and if you hear “The tuba was played by Alice

you

remember “Alice play tuba + passive”. The “+ passive” part refers

to the fact that the sentence you heard was in the passive voice,

otherwise,

you couldn't tell that from the representation. There's evidence

that when you have people recall sentences, they generally forget

transformations

more than meaning. We saw a little of this last time.

C. Propositional representation. Propositions are like

the idea units in a text. For example, the structure of “The

professor

delivers the boring lecture” would include:

P1: Exists(professor)

P2: Exists(lecture)

P3: Boring(P2)

P4: Deliver(P1, P2)

We'll see a more formal propositional system a little later.

Evidence:

1. That you go beyond verbatim representation:

Sachs (1967) presented a story about telescopes. During reading,

if you test immediately after a sentence, people recognize changes in

the

surface structure of the sentences as readily as changes in

meaning.

After 80 syllables, however, people recognize changes in meaning, but

not

changes in surface structure. Sentence (1) below is the

original.

After 80 syllables, (1) - (3) are all recognized at about the same

percentage.

(1) He sent a letter about it to Galileo,

the great Italian scientist.

(2) He sent Galileo, the great Italian

scientist,

a letter about it.

(3) A letter about it was sent to Galileo,

the great Italian scientist.

(4) Galileo, the great Italian scientist,

sent him a letter about it.

This finding is usually interpreted as demonstrating that you retain

the basic ideas more than the exact words.

2. That you have propositions:

Many studies show that what people forget from sentences tend to be

whole propositions. Furthermore, varying the number of

propositions

per sentence is a much more effective way of increasing the difficulty

of a text than varying the number of words.

Top

IV. Inferences. Inferences go beyond literal meaning

by adding something to the representation of the text that wasn't in

the

text. To see what an inference is, try the demonstration.

Demonstration: Read these two sentences. To

understand

how they relate, you have to make an inference along the lines of

“riding

a bike is a way to lose weight.” In general, making inferences is

so easy that you probably don't even know you're doing it.

(5) Diane wanted to lose some weight.

(6) She went to the garage to find her bike.

I'll present a scheme for classifying inferences along four dimensions.

A. Logical vs. pragmatic inferences: Some inferences are

guaranteed to be correct (if you form them). So, if you hear

“Todd

has six apples, he gave three to Susan”, it's safe to infer that Todd

has

three apples (logical inference). On the other hand, some

inferences

are likely, but not guaranteed (pragmatic). So if you hear “Todd

dropped the egg”, you don't know for sure that it broke (but it

probably

did).

B. Forward vs. backward: Some inferences are made in

advance.

For example, if you hear “John pounded the nail” and infer “John used a

hammer,” it's forward. Other inferences are made about past

things.

For example, if you read “John pounded the nail. The handle broke

and he smashed his thumb,” you need to infer “hammer” to figure out

what

handle broke. Backward inferences are generally called bridging

because

they build a bridge between two parts of the text to explain how you

get

from one to the other. Forward inferences are usually elaborative

because they elaborate on the text but aren't strictly necessary.

C. Type of inference: There are five types here:

1. Case-filling: In your case-role grammar you can infer

parts that are missing. For example, if you hear “Father carved

the

turkey” you can fill in the instrument (like knife).

2. Event-structure: If you read “The actress fell from

the 14th floor balcony” you might infer the consequence (she

died).

Or, you might infer a cause (she slipped). These are things that

flesh out the structure of an event.

3. Parts: If I say “Carol entered the room. The X

was dirty”, you might infer “the room has an X.” Usually, these

are

required to make sense of a text. For example, if you read “He

poured

the tea and burned his hand on the handle” you need to infer a teapot

handle

to make sense of it.

4. Script: People have scripts for prototypical

event-sequences

(like going to a restaurant). Script inferences are when they

fill

in missing events with items from the script.

5. Spatial/temporal: You can infer relationships between

items in a text. For example, if I say “B is to the left of A”,

you

might infer “A is to the right of B.”

D. Implicational probability: How strongly is the inference

implied by the text. Some things are much more likely than

others.

For example, floors are more likely in rooms than chandeliers.

When we look at our model of understanding we'll see that inferences

have a major role to play.

Top

V. Figurative language. The meaning is completely

different from the words used to convey it. I'll just list some

of

the more common types.

A. Metaphor: “John is a pig” You know John isn't

actually a pig, the meaning somehow relates features of pigs to

features

of John.

B. Idioms: “Spill the beans.” It's like a

conventionalized

metaphor. In terms of comprehension, it's treated like a big

word.

For example, “spill the beans” = “tell a secret.”

C. Metonymy: “Washington and the Kremlin are finally

talking.”

Let some aspect stand for the whole. For example, we let the fact

that the US government is in Washington stand for the whole government.

D. Colloquial tautologies: “Boys will be boys.” It's

a kind of metonymy where some feature is highlighted. It's

usually

negative (as in “business is business”), but for objects it's also

indulgent.

So, you'll hear “boys will be boys”, but not “rapists will be rapists.”

E. Irony/sarcasm: The words are used to express a situation

that's actually opposite from the words. For example, if

someone's

lounging on the couch and you come in and say “Boy, you're working

hard.”

Figurative language represents a special case for reading, because

we have to get from one set of words to a different set of

meanings.

How it's done is an interesting challenge for our methodology.

Top

VI. Pragmatics. Speaker and hearers' background

beliefs, understanding of the context, and knowledge of the way

language

is used to communicate. Note that none of this stuff is literally

in the message. Consider:

(7) The councilors refused the marchers a

parade permit because they feared violence. (who fears?)

(8) The councilors refused the marchers a

parade permit because they advocated violence. (who advocates?)

The information about who fears and who advocates comes more from your

knowledge about councilors and marchers, not as much from the sentence.

I'm going to lump a lot of diverse language activities under this

umbrella

for want of a better place to put them. The thing they have in

common

is that the meaning is derived as much from external factors as from

the

message.

A. Presuppositions: An assumption or belief is implied

by the choice of a particular word. Consider:

(9) Have you stopped exercising regularly?

(10) Have you tried exercising regularly?

“Stopped” implies that you used to exercise, “tried” implies that you

don't exercise. It's possible that in some contexts this will

even

lead to a person being insulted.

B. Speech acts: The effect of the message is different

from its literal content. There are 3 parts:

1. The locutionary act: The utterance.

2. The illocutionary act: What's intended by the speaker.

3. The perlocutionary act: The effect.

If I said “Can you shut the blinds?”: L = “Are you able to shut

the blinds?”, I = “Please shut the blinds”, P = someone shuts the

blinds.

Speech acts can take numerous forms:

1. Statement: “There's a bear behind you.”

2. Command: “Run!”

3. Yes/No question: “Did you know there's a bear behind

you?”

4. Wh- question: “What's that bear doing in here?”

The form can have an impact on the perlocutionary act.

Understanding: What does it mean to understand?

Again, hard to say. Try this demonstration.

Demonstration: Read the two passages. One should

seem easy to understand, one should be hard. By the end of this

unit,

we should be on our way to quantifying why that is.

"Weighing less than three pounds, the human brain in its natural state

resembles nothing so much as a soft, wrinkled walnut. Yet despite

this inauspicious appearance, the human brain can store more

information

than all the libraries in the world. It is also responsible for

our

most primitive urges, our loftiest ideals, the way we think, even the

reason

why, on occasion, we don't think, but act instead. The workings

of

an organ capable of creating Hamlet, the Bill of Rights, and Hiroshima

remain deeply mysterious."

"On the other hand, there may be portions of this task which can be

formulated without reference to numerical relationships, i.e. in purely

logical terms. Thus certain qualitative principles involving

physiological

response or nonresponse can be stated without recourse to numbers by

merely

stating qualitatively under what combinations of circumstances certain

events are to take place and under what combinations they are not

desired."

As we do this unit, we'll focus on readers’ knowledge, because what

you already know is a big influence on what you understand. Then,

we'll look at a model of understanding to see how it might work.

There will be several parts to that.

Top

VII. Readers’ knowledge. You have a lot of world

knowledge that you can bring to bear when reading. That knowledge

will greatly influence how well you understand the text. One type

of knowledge is script knowledge. For a lot of overlearned event

sequences, you know what typically happens. We talked about going

to the doctor's office before. When you're trying to understand a

story, one thing you're doing is matching it to a script. If you

know a lot about doctors, you can fill in details from the story to

improve

comprehension. You can also use the script to help you remember

the

story later. There are also scehmas. These are knowledge

structures.

For example, you should be developing a cognitive psychology

schema.

How can these affect comprehension?

A. A prior context is one way to improve comprehension.

Basically, knowing which script (or schema) to apply will help you

understand.

Demonstration: One of these passages follows a typical

script, one follows a schema. Read this passage. Brief

retention

interval. Write down all you recall. Memory should be

poor.

Now, the title is “suppressed so my demonstration works.”

Recall.

Does it help? Try reading it again with the title.

Recall.

Does it help?

A second try: Half get “title suppressed” half don't.

Everyone

read the passage and recall. Who gets more?

What usually happens is that prior context helps with memory because

it gives you a way to organize the information. Without a

context,

it's very hard to make sense of the texts, and memory is poor.

B. A problem is: If all you're doing is remembering the

script, how do you tell individual events apart? An easy answer

is

that you usually don't. What did you have for breakfast a year

ago

today? Most people have no idea how to answer this

question.

In experiments, people will frequently “remember” things that are

typical

of a script, but not in the text they read.

Demonstration: Half the people read about Guy 1, half

read about Guy 2. After a longish retention interval, the Guy 2

people

are more likely to falsely recognize sentences about Guy 2 than the Guy

1 people.

Half the people read about Guy 1, half read about Guy 2. Then,

after a week, they were asked to recognize statements. The Guy 2

group was more likely to falsely recognize statements like “sorry, it's

a secret.” The point is that when recalling, prior knowledge is

integrated

with what you are learning. To the extent you have prior

knowledge,

reading isn't all that hard. When the knowledge is missing,

reading

gets tougher.

C. It's not just scripts and prior context that can provide the

necessary knowledge to make a text comprehensible.

Demonstration: Read this passage. Now, try it with

the picture. It should make more sense and be easier to remember.

The point of this section so far is clear. If you have something

to use as the foundation of your representation, good. If not,

it's

hard. Some of the material for this class should present you with

these kinds of problems because of a lack of prior knowledge.

Top

VIII. Working memory revisited. As you've probably

noticed, working memory plays a big role in almost every model of

comprehension,

at every level. How does it affect language comprehension?

It acts as a limit on how much you can hold at once.

When you get an item that you want to include, you have to gather some

activation (akin to “mental energy”) that you can use to represent

it.

Putting something in working memory takes mental effort. If you

don't

work at it, it won't happen. Unfortunately, the amount of mental

energy that you have at your disposal is fixed (when we talk about

working

memory capacity, that's the capacity).

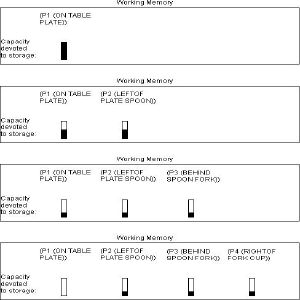

Let's say you're processing this sample of text:

The plate is on the table.

The spoon is left of the plate.

The fork is behind the spoon.

The cup is right of the fork.

Let's further assume that your working memory capacity is three things

(plus processing load). (This will make more sense if you follow

along with the figure.) When you get the first proposition, you

can

give it all of your storage capacity. When the next proposition

comes

in, you have to steal some activation to represent it. So, they

both

get in, but they're each half as strong as the first one was.

Then

the third proposition comes in. You steal some more activation,

and

put it in.

When the fourth proposition comes along, you're out of juice.

Now, when you steal activation, something has to go.

Working memory limitations are a driving force behind theories of

language

comprehension. Last time we discussed parsing strategies like

late-closure

to ease the burden. The models of understanding also have working

memory limitations.

Top

IX. Outline of a basic discourse model. The basic

problem in text comprehension is that the meaning of a text is more

than

the meanings of its sentences. Somehow, you have to connect

information

in the sentences into a coherent structure that is the “meaning” of the

text. The Kintsch and vanDijk (1978) model illustrates all of the

basic parts of this process.

A. There are four main steps in comprehending texts. They

are:

1. Turn the text into propositions. There's a fully

developed

system for this. Here's an example of a basic proposition, just

to

get the flavor:

(P1 (WANTS JOAN APPLE))

The parts:

a. P1: This is the proposition number. Propositions

can be embedded in propositions, as in (P2 (TIME:IN P1

YESTERDAY)).

The numbering system acts as an embedding shorthand.

b. WANTS: A relation. The word is in all caps to

indicate that it's a concept, not a word. So, propositions are

supposed

to be in the “language of thought,” not tied to a particular

language.

WANTS could just as easily be AS1295D.

c. JOAN APPLE: Arguments. These are what the relation

is about. Some relations need two arguments, some need just

one.

The number of arguments is based on the same considerations we

discussed

when we talked about verbs and cases. It's unusual to say “I

gave”

because “give” normally requires an object to be given.

The first step is to take an entire text and turn it into propositions.

2. Arrange the propositions into a text base: An organized

representation of the text (but only a local representation, meaning it

covers relationships between ideas that are close together). It

will

look a lot like our phrase markers from last week, but we're connecting

concepts and not syntactic categories.

Some propositions appear more often (they're important to the story

so they stay in working memory).

3. Use world knowledge to form global concepts (akin to

identifying

the main ideas).

4. Form a macrostructure: The relationships between the

units in the text base. Essentially, connect the smaller trees

into

a super-tree. World knowledge helps a lot with this as well.

Demonstration: To illustrate these concepts, look at these

samples of text. The one that's locally and globally consistent

should

be easy to understand because you can connect each new sentence to an

old

sentence, and there's a global structure. The one that's locally

inconsistent stays on a topic, but connecting each sentence is hard

because

inferences are required. The last one is easy to do locally, but

has a problem in its macrostructure. In general local problems

are

harder for readers than global problems. In fact, readers usually

don't notice global problems. The model takes this into account.

Locally and globally consistent

George wanted to run in a marathon.

Running requires a lot of energy, and this energy can come from

carbohydrates.

Spaghetti has a lot of carbohydrates, so George learned how to make

spaghetti.

Eating spaghetti helped George have the energy he needed to finish

the marathon.

Locally inconsistent

Diane wanted to lose some weight.

She went to the garage to find her bike.

Diane's bike was broken and she couldn't afford a new one.

She went to the grocery store to buy grapefruit and yogurt.

Globally inconsistent

Tammy was standing inside the health spa waiting for her friend.

She had just completed an exhausting workout.

Tammy's workout usually included a half hour of aerobics and an hour

of weight training.

Today, Tammy had doubled her aerobics time.

Tammy saw her friend and went into the health spa to greet her.

B. Some additional notes on the model:

1. Readability is characterized by properties of the text and

properties of the reader. For example, if the text is well

constructed,

but your memory is low, then you'll have a hard time building

structures.

Or, if the text is poor, but memory is high, you'll still struggle.

2. How do they test this model? They present the passages

to the model and look at its memory. The model's recall of a text

is based on how often a proposition was held over in working memory,

how

related propositions are to one another, how easy it was to form

structures,

etc.

They also present these passages to human participants and look at

their recall. If people tend to remember similar propositions in

a similar order, that's evidence that the model is using a similar

process.

3. This model has all the parts:

a. Levels of representation (we talked about this in the last

unit).

b. Limited working memory capacity.

c. Strategies to choose what to remember.

d. Influences of readers’ knowledge.

Top

X. Mental models. So far, our readers are extracting

propositions, building local structures, identifying topics, and making

global structures. Is there anything else going on?

Yes.

In addition to all of this, readers are forming mental models of the

events

in a text. A mental model is a representation of what the text is

about, not the text itself. So, it goes beyond propositions (a

representation

of the text).

A. Where is it? Remember that we talked about divisions

in working memory, and two main branches. You have an

articulatory

loop and a visuo-spatial scratchpad. The loop holds auditory

information

(either from hearing speech or recoding written text). The

sketchpad

is for images, processing pictures, and doing spatial things like

moving

your eyes across the page and processing visual features of text.

It's not so much a place as a kind of mental energy devoted to spatial

processing. All of the stuff we've discussed so far goes on in

the

loop, the mental model is in the sketchpad.

B. What do I mean by a model? Read the first two sentences

about turtles and logs. They both describe the same

situation.

If you read the first one and I give you the second one to verify, what

will happen? Now, look at the second two. They describe

different

situations. If I give you the first one and ask you to verify the

second one, what will happen?

(11) Three turtles rested on a floating log

and a fish swam beneath them.

(12) Three turtles rested on a floating log

and a fish swam beneath it.

(13) Three turtles rested beside a floating

log and a fish swam beneath them.

(14) Three turtles rested beside a floating

log and a fish swam beneath it.

The difference in terms of propositions is very slight. In fact,

the difference that distinguishes the sentences in the two situations

is

the same. So, there must be some additional level of

representation

that explains this. That's the mental model.

C. What do mental models do? One thing is keep information

foregrounded (show you that it's with the topic and should remain in

working

memory). Glenberg, Meyer, and Lindem (1987) demonstrated

this.

People read texts like this sample. At some point, they saw a

word

and had to say if that word was in the text. The trick was that

the

item could sometimes be associated with the main character (so it goes

where the main character goes) and other times dissociated (the

character

goes somewhere, the item stays behind). Associated items should

stay

foregrounded because they might come up again. Dissociated items

can usually be forgotten safely. A demonstration of this

experiment

is available on my software page.

If readers are forming a mental model, then associated items would

be near the character in the model, and dissociated items would be far

away. Being near should facilitate responding to the test.

If you look at the graph of the data, you can see that that

happens.

Associated items are more readily available after a one sentence delay

than dissociated items.

Top

XI. Wrap-up. What we've done is looked at how all

of our cognitive psychology tools could be brought to bear on

understanding

what you read and defining the meaning of what you read.

Obviously,

there's still more to it. But, this gives you an idea of how the

representations and processes discussed so far can aid in comprehension

of complex cognitive activities. For more, take the language

class

in the fall.

Top

Cognitive Psychology Notes 12

Will Langston

Back to Langston's Cognitive Psychology

Page