Langston,

Psychology of Language, Notes 7 -- Syntax

I. Goals:

A. Introduction.

B. Formal grammars.

C. Parsing strategies.

II. Introduction. We've discussed decoding processes

(getting from sounds and letters to words), but we still haven't done

anything

with the stuff we've decoded. I want to emphasize a couple of

basic

themes:

A. Language things can be described by a grammar (a set of

elements

and rules for combining those elements). As an exercise, we

should

review the elements and rules we know about so far:

1. Perceiving speech.

2. Reading.

3. Meanings.

B. Language is frequently understood in spite of a lot of

ambiguity.

During comprehension, something has to be done to resolve

ambiguity.

You can take two approaches:

1. Brute force: Represent every possibility. For

lexical access, this seems to be what happens. If someone reads

"He

dug with the spade," "Shovel" and "ace" are equally activated.

The

wrong meaning is quickly suppressed. There are good reasons for

lexical

access to work this way, and it seems to be the only process that uses

brute force.

2. Immediacy assumption: Make a choice, try to go on, if

you get stuck, reevaluate. As we start to get into syntax, you'll

see why this has to happen. There are too many possibilities to

maintain

all of them.

As an exercise, let's rehearse some of the ambiguities we've seen so

far:

1. Perceiving speech.

2. Reading.

3. Meanings.

C. Now we come to the point where things get exciting.

Language usually comes at us in sentences, and that's our next level of

analysis. What is the meaning of a sentence? There are

three

parts: Syntax (the rules for grammar); Semantics (the rules for

combining

units of meaning); and Pragmatics (extra-linguistic knowledge that

helps

you interpret the content of a message). We'll address each in

turn.

To start grammar, I want you to try a couple of exercises that will

get at our basic themes:

1. Write down the meaning of "of." It should be hard

because

it represents an empty syntactic category, and not a word.

2. What is the meaning of this sentence: "The boy saw the

statue in the park with the telescope." Could the statue have the

telescope? Could the boy be in the park? This is a kind of

syntactic ambiguity.

Top

III. Formal grammars.

A. Word string grammars (finite state grammars): Early

attempts to model sentences treated them as a string of

associations.

If you have the sentence "The boy saw the statue," "the" is the

stimulus

for "boy," "boy" is the stimulus for "saw,"... If a speaker is

processing

language, the initial input is the stimulus for the first word, which,

when spoken, becomes the stimulus for the next word, ...

These ideas get tested with "sentences" of nonsense words. If

you make people memorize "Vrom frug trag wolx pret," and then ask for

associations

(by a type of free association task), you get a pattern like this:

| Cue |

Report |

vrom

frug

trag |

frug

trag

wolx... |

It looks like people have a chain of associations. This is

essentially

the behaviorist approach to language.

Chomsky had three things to say in response to this:

1. Long distance dependencies are problematic. A long

distance

dependency is when something later in a sentence depends on something

earlier.

For example, verbs agree in number with nouns. If I say "The dogs

that walked in the grass pee on trees," I have to hold in mind that

plural

"dogs" take the verb form "pee" and not "pees" for five words.

Other

forms of this are sentences like "If...then..." and

"Either...or..."

In order to know how to close them, you have to remember how you opened

them.

2. Sentences have an underlying structure that can't be

represented

in a string of words. If you have people memorize a sentence like

"Pale children eat cold bread," you get an entirely different pattern

of

association:

| Cue |

Report |

pale

children

eat

cold

bread |

children

pale

cold or bread

bread

cold |

Why? "Pale children" is not a pair of words. It's a noun

phrase. The two words produce each other as associates because

they're

part of the same thing. To get a representation of a sentence,

you

need to use (at least) a phrase structure grammar. That's our

next

proposal.

3. Something can be a sentence with no associations.

"Colorless

green ideas sleep furiously" still works as a sentence, even though you

probably have no association between colorless and green.

B. Phrase structure grammars (a.k.a. surface structure

grammars):

Generate a structure called a phrase marker when parsing (analyzing the

grammatical structure of the sentence). It proceeds in the order

that the words occur in the sentence, and the process is to

successively

group words into larger and larger units (to reflect the hierarchical

structure

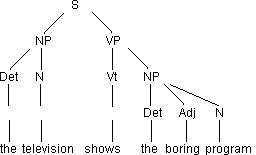

of the sentence). For example:

(1) The television shows the boring program

The phrase marker is a labeled tree diagram that illustrates the

structure

of the sentence. The phrase marker is a result of the parsing.

What's the grammar? It's a series of rewrite rules. You

have a unit on the left that's rewritten into the units on the

right.

For our grammar (what we need to parse the sentence above) the rules

are:

P1: S -> NP VP

P2: VP -> V NP

P3: NP -> Det (Adj)* N

L1: N -> {television, program}

L2: Det -> {the}

L3: V -> {shows}

L4: Adj -> {boring}

The rules can be used to parse and to generate.

C. Transformational grammars: There are some constructions

you can't handle with phrase structure grammars. For example,

consider

the sentences below:

(2) John phoned up the woman.

(3) John phoned the woman up.

Both sentences have the same verb ("phone-up"). But, the "up"

is not always adjacent to the "phone." This phenomenon is called

particle movement. You can't parse or generate these sentences

with

a simple phrase-structure grammar. Problems like this were part

of

the motivation for transformational grammar's development.

Chomsky

is also responsible for this insight.

What is transformational grammar? Add some concepts to our

phrase-structure

grammar (both technical and philosophical):

1. The notion of a deep structure: Sentences have two

levels

of analysis: Surface structure and deep structure. The

surface

structure is the sentence that's produced. The deep structure is

an intermediate stage in the production of a sentence. It's got

the

words and a basic grammar.

2. Transformations: You get from the deep structure to

the surface structure by passing it through a set of transformations

(hence

the name transformational grammar). These transformations allow

you

to map a deep structure onto many possible surface structures.

3. Expand the left side of the rewrite rules:

Transformation

rules can have more than one element on the left side. This is a

technical point, but without it you couldn't do transformations.

Why do we need to talk about deep structure? It explains two

otherwise difficult problems:

1. Two sentences with the same surface structure can have very

different meanings. Consider:

(4a and 4b) Flying planes can be dangerous.

This can mean either "planes that are flying can be dangerous" or

"the

act of flying a plane can be dangerous." If you allow this

surface

structure to be produced by two entirely different deep structures,

it's

no problem.

2. Two sentences with very different surface structures can have

the same meaning. Consider:

(5) Arlene is playing the tuba.

(6) The tuba is being played by Arlene.

These both mean the same thing, but how can a phrase structure

grammar

represent that? With a deep structure (and transformations) it's

easy.

Let's get into this with Chomsky's (1957) Toy Transformational

Grammar.

His model has four basic stages:

Phrase structure rules allow you to construct basic trees (what we've

already seen). Then lexical insertion rules put on the

words.

That makes a deep structure. Then, you do some

transformations.

Finally, you go through a pronunciation stage and you have the surface

structure, or the final sentence.

The rules (different for each stage):

a. Phrase structure rules:

P1: S -> NP VP

P2: NP -> Det N

P3: VP -> Aux V (NP)

P4: Aux -> C (M) (have en) (be

ing)

b. Lexical insertion rules:

L1: Det -> {a, an, the}

L2: M -> {could, would, should,

can, must, ...}

L3: C -> {ø, -s (singular

subject), -past (abstract past marker), -ing (progressive), -en (past

participle),

...}

L4: N -> {cookie, boy, ...}

L5: V -> {steal, ...}

c. Transformation rules:

Obligatory

T1: Affix (C) V -> V Affix

(affix hopping rule)

Optional

T2: NP1 Aux V NP2 -> NP2 Aux be en

V by NP1 (active ->

passive transformation)

d. Morpho-phonological rules:

M1: steal Æ /stil/

M2: be Æ /bi/ etc.

How does this work? I've done an example for "The boy steals

the cookie." (Tree given in class)

Produce the sentence "The boy steals the cookie." (Tree given

in class)

Here's a harder one because it involves the passive. Produce

"The cookie is stolen by the boy." (Tree given in class)

You try "The cookie could have been being stolen by the boy" as an

exercise.

Psychological evidence for transformations. Early studies rewrote

sentences into transformed versions. For what follows, the base

sentence

is "the man was enjoying the sunshine."

Negative: "The man was not enjoying the sunshine."

Passive: "The sunshine was being enjoyed by the man."

Question: "Was the man enjoying the sunshine?"

Negative + Passive: "The sunshine was not being enjoyed by the

man."

Negative + Question: "Was the man not enjoying the sunshine?"

Passive + Question: "Was the sunshine being enjoyed by the man?"

Negative + Passive + Question: "Was the sunshine not being

enjoyed

by the man?"

I have you read lots of these and measure reading time. The more

transformations you have to undo, the longer it should take. That

happens. Note the problem with unconfounding reading time from

the

number of words in the sentence.

D. Semantic grammars: The PSG and transformational grammars

parse sentences with empty syntactic categories. For example, NP

doesn't mean anything, it's just a marker to hold a piece of

information.

These syntax models have some problems:

1. Not very elegant. The computations can be pretty

complicated.

2. Overly powerful. Why this set of transformations?

Why not transformations to go from "The girl tied her shoe" to "Shoe by

tied is the girl"? There's no good reason to explain the

particular

set of transformations that people seem to use.

3. They ignore meaning. Chomsky's sentence "They are

cooking

apples" isn't ambiguous in a story about a boy asking a grocer why he's

selling ugly, bruised apples. Sentences always come in a context

that can help you understand them.

Semantic grammars are different in spirit. The syntactic

representation

of a sentence is based on the meaning of the sentence. For

example,

consider Fillmore's (1968) case-role grammar. Cases and roles are

the parts each element of the sentence plays in conveying the

meaning.

You have roles like agent and patient, and cases like location and

time.

The verb is the organizing unit. Everything else in the sentence

is related to the verb. Consider a parse of:

(7) Father carved the turkey at the Thanksgiving dinner

table with his new carving knife.

The nodes here have meaning. You build these structures as you

read, and the meaning is in the structure. You can do things

purely

syntactic grammars can't. For example, consider:

(8) John strikes me as pompous.

(9) I regard John as pompous.

If you analyze these two syntactically, it's hard to see the

relationship

between the "me" in (8) and the "I" in (9). But, there is a

relationship.

Both are the experiencer of the action. One problem is the number

of cases.

E. Something to keep in mind: Competence vs.

performance.

People have pushed each of these to generate and comprehend language

(I've

used a modified PSG to read and write scripts for Friday the 13th

movies).

But, that's only demonstrating competence: being capable of

solving

the problem. It doesn't address performance: What people

actually

do. The question of what people actually do hasn't been

determined.

We might agree that some form of syntactic analysis has to take place,

and we might agree that these grammars can achieve that, but that isn't

saying we agree on performance.

Top

IV. Parsing strategies. When people are reading

text, how do they parse on the fly?

A. Some constraints on parsing: People have a very limited

capacity working memory. This means that any processes we propose

have to fit in that capacity. The problem of trying to do it with

limited resources will be the driving force behind the

strategies.

They're both ways to minimize working memory load. One way to

minimize

load is to make the immediacy assumption: When people encounter

ambiguity

they make a decision right away. This can cause problems if the

decision

is wrong, but it saves capacity in the meantime. Consider a

seemingly

unambiguous sentence like:

(10) John bought the flower for Susan.

It could be that John's giving it to Susan, but he could also be buying

it for her as a favor. The idea is that you choose one right

away.

Why? Combinatorial explosion. If you have just four

ambiguities

in a sentence with two options each, you're maintaining 16 possible

parses

by the end. Your capacity is 7±2 items, you do the

math.

To see what happens when you have to hold all of the information in a

sentence

in memory during processing, try to read:

(11) The plumber the doctor the nurse met called ate the

cheese.

The problem is you can't decide on a structure until very late in the

sentence, meaning you're holding it all in memory. If I

complicate

the sentence a bit but reduce memory load, it gets more comprehensible:

(12) The plumber that the doctor that the nurse met called

ate the cheese.

Or, make it even longer but reduce memory load even more:

(13) The nurse met the doctor that called the plumber that

ate the cheese.

Now that we've looked at the constraints supplied by working memory

capacity and the immediacy assumption, let's look at the strategies.

B. Parsing strategies. There are two problems. The

first is getting the clauses, the second is hooking them up.

1. Getting the clauses (NPs, VPs, PPs, etc.).

a. Constituent strategy: When you hit a function word,

start a new constituent. Some examples:

Det: Start NP.

Prep: Start PP.

Aux: Start VP.

b. Content-word strategy: Once you have a constituent

going,

look for content words that fit in that constituent. An example:

Det: Look for Adj or N to follow.

c. Noun-verb-noun: Overall strategy for the sentence.

First noun is agent, verb is action, second noun is patient.

Apply

this model to all sentences as a first try. Why? It gets a

lot of them correct. So, you might as well make your first guess

something that's usually right. We know people do this because of

garden-path sentences (sentences that lead you down a path to the wrong

interpretation). Example:

(14) The editor authors the newspaper hired liked

laughed.

You want authors to be a verb, but when you find out it isn't, you

have to go back and recompute.

d. Clausal: Make a representation of each clause, then

discard the surface features. Evidence:

(15) Now that artists are working in oil prints are

rare.

(863 ms)

vs.

(16) Now that artists are working longer hours oil prints

are rare. (794 ms)

In 15, "oil" is not in the last clause, in 16 it is. The access

time for "oil" after reading the sentence is in parentheses. When

it's not in the current clause, it takes longer, as if you've discarded

it.

2. Once you get the clauses, how do you hook them

up? More strategies:

a. Late closure: The basic strategy is to attach new

information

under the current node. Consider the parse for:

(17) Tom said Bill ate the cake yesterday.

(We'll need some new rules in our PSG to pull it off, I'm skipping

those to produce final phrase markers.)

Late Closure and Not Late Closure trees go here.

According to late closure, "yesterday" modifies when Bill ate the cake,

not when Tom said it (is that how you interpreted the sentence?)

It could modify when Tom said it, but that would require going up a

level

in the tree to the main VP and modifying the decision you made about it

(that it hasn't got an adverb). That's a huge memory burden (once

you've parsed the first part of the sentence, you probably threw out

that

part of the tree to make room). So, late closure eases memory

load

by attaching where you're working without backtracking.

Evidence: Have people read things like:

(18) Since J. always jogs a mile seems like a very short

distance to him.

With eye-tracking equipment, you can see people slow down on "seems"

to rearrange the parse because they initially attach "a mile" to jogs

when

they shouldn't.

b. Minimal attachment: Make a phrase marker with

the fewest nodes. It reduces load by minimizing the size of the

trees

produced. Consider:

(19) Ernie kissed Marcie and Joan...

Minimal Attachment and Not Minimal Attachment trees go here.

The minimal attachment tree has 11 nodes vs. 13 for the other.

It's also less complex. The idea is that if you can keep the

whole

tree in working memory (you don't have to throw out parts to make

room),

then you can parse more efficiently.

Evidence: Consider:

(20) The city council argued the mayor's position

forcefully.

(21) The city council argued the mayor's position was

incorrect.

In (21) minimal attachment encourages you to make the wrong tree and

you have to recompute.

3. Note that these are strategies. Both help you meet the

goal of keeping your burden as small as possible. It doesn't mean

this is all you do or that these necessarily compete during processing.

Top

Psychology of Language Notes 7

Will Langston

Back to Langston's Psychology of Language

Page